Your Custom Text Here

“Systems cannot be controlled, but

they can be designed and

redesigned.”

- Donella Meadows

Access to high-quality early childhood education is vital to the future of our children and our communities.

Even if you don’t have a child, the benefits of a high-quality system extend to the entire community by way of a more productive workforce (Campbell et al., 2008), decreased crime rates (Bongers et al. 2008; Garcia et al., 2017; Heckman & Karapakula, 2019) and intergenerational stability of families (Heckman & Karapakula, 2019).

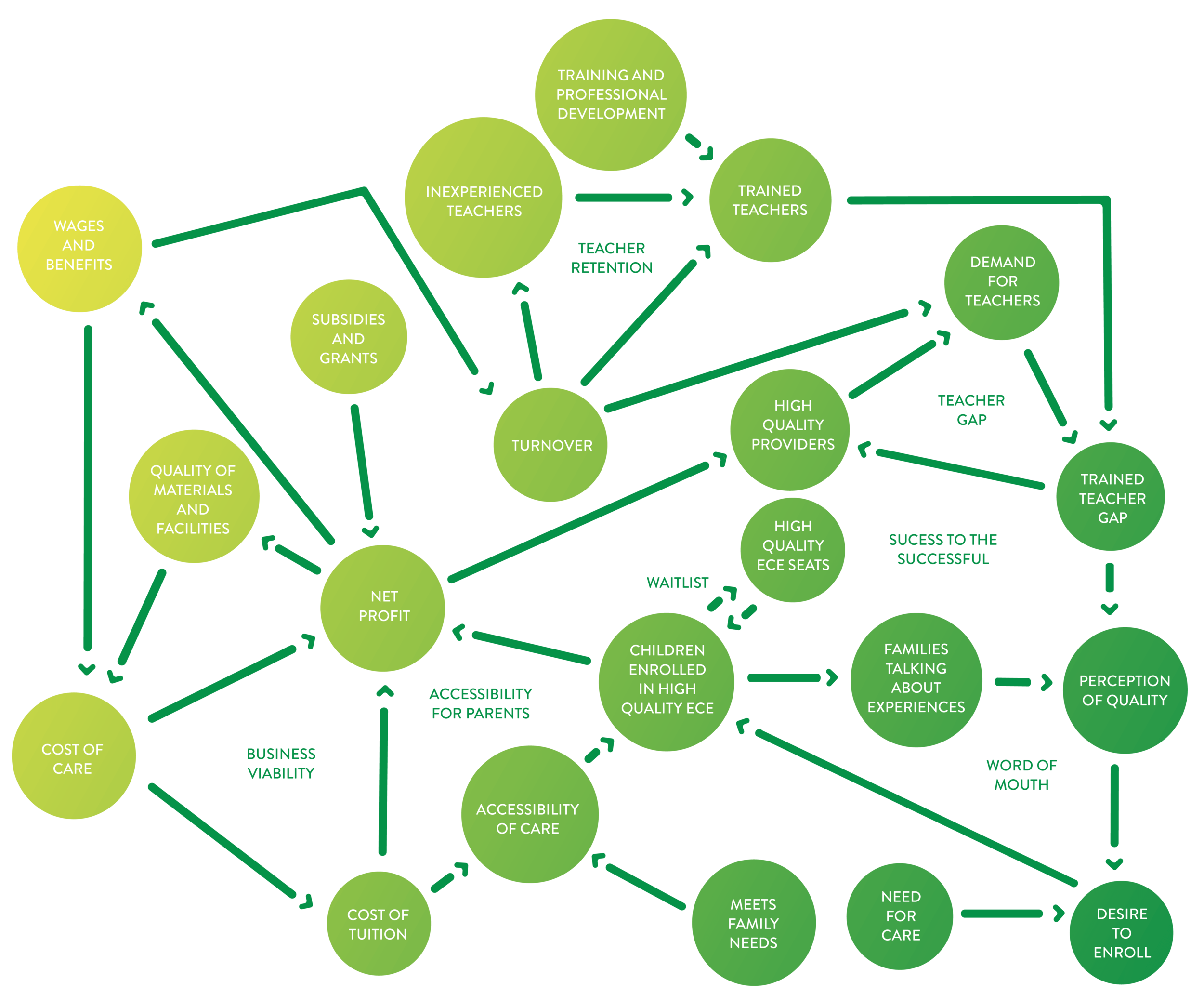

In St. Louis’ ECE system, fundamental components of ECE including equity, quality, and the business viability of delivering high-quality early education are in conflict. Parents struggle to afford high-quality ECE in a system they don’t trust. Workers turn over at high rates, while providers struggle to compensate teachers without increasing tuition costs for families.

With limited resources and much to do, we must prioritize work that offers the highest possible leverage to shift current dynamics. The suggestions outlined below are a result of modeling insights from a two-year comprehensive study of the early childhood system in St. Louis. A computer simulation model was developed from insights using qualitative interviews with parents, teachers, researchers, and ECE providers. Quantitative data paired with system dynamics was used to test the model’s robustness and utility. While these insights are neither comprehensive nor silver bullets, without prioritizing these interventions, we risk spending dollars on actions that may moderately improve the system for some, but will not ultimately lead to the broad system we all desire.

Prioritize Worker Turnover

Well-trained, engaged teachers and staff are at the heart of a child’s education. For many providers trying to create high-quality programs, hiring a sufficient number of workers who can provide high-quality ECE is an insurmountable obstacle.

Professional development and building professional pathways for people to enter the field are important. Until we can stem the flood of workers leaving the field, however, the resources poured into bringing people into the field and training them will be lost as staff turn over each year. Decreasing workforce turnover should be one of the first priorities when it comes to intervention and developing strategic initiatives.

Bring in New Funding

Increasing compensation for workers is a key component of decreasing turnover. In the current system, providing higher salaries and better benefits will force many providers out of business. Some may be able to charge higher tuition to offset the increased costs, but in doing so, many more families will no longer be able to afford care, increasing the inequities in the system. St. Louis needs sustained funding for our ECE system in order to provide competitive wages to ECE workers without passing the costs on to families or providers.

This is true for other interventions that would benefit the regional system. Increasing access to professional credentials, programs to help providers become licensed and accredited, and increasing subsidies and reimbursement rates all cost money. Parents and providers in the ECE field cannot bear the burden of these costs - balancing affordability for families and paying for the cost of care already strain both parties. Installing new funding mechanisms to defray the costs of interventions is vital to the success of those interventions and avoids harming providers, families, and workers.

Increase Accessibility and Quality in Tandem

High-quality ECE is not accessible for most families in St. Louis. Increasing affordability and opening up new spots in programs that meet families’ needs is rightly high priority for many looking to improve the ECE system. However, this must be done in tandem with increasing the quality of ECE in the region to avoid negative word of mouth. If more spots are open and affordable but are not staffed by teachers who can provide high-quality education, families who do enroll will have negative experiences. Negative word of mouth will spread as those families talk to other parents and guardians about their experiences, increasing mistrust in the ECE system and making parents and guardians less likely to enroll overall.

This is true for other interventions that will drive demand without increasing quality. For example, a marketing campaign about the importance of enrolling in ECE could backfire if quality has not improved across the region. More families might enroll their children in ECE, but over time, the negative experiences of those families will erode trust in both the ECE programs and future marketing campaigns.

However, if you just increase the number of high-quality spots available without increasing accessibility, only high-resource families will be able to enroll their children. This will add to the inequities that already exist in the ECE system.

Lastly, if you increase quality and accessibility without increasing the number of spots available, this will generate demand that cannot be met. As families talk about their positive experiences, more families will want to enroll, putting further pressure on an already-strained system. Waitlists and frustrations will increase. This is the current reality for many high-quality providers. Some have years-long waitlists, especially those who have managed to keep care affordable through donations and grants. While this may be an inevitable part of change and preferable to the unintended consequences discussed above, acknowledging the potential frustrations that may come is an important first step in planning how to move forward.

It is important to consider the extent of work that will be needed to expand access to high-quality ECE for all families. While many of efforts around expanding accessibility have been focused on families who qualify for subsidies, the reality is that a large gap exists between the cutoff for subsidies at 138% of the federal poverty line and the $228,800 annual income it would take for a family of four to be able to comfortably afford ECE, especially in an area where the median household income is $61,571 per year. It is vital that we decrease the cost of ECE to families as a whole while still paying providers enough to provide high-quality care.

Define and Measure Quality

The region lacks both a shared definition of quality and comprehensive, longitudinal data about ECE. In our research, we made some simple assumptions about high-quality ECE: it requires highly trained and engaged workers and enough resources to provide certain components like good food and safe environments, but we remained agnostic about the other components of quality. While this might work in a computer simulation, in order to train teachers and staff to provide high-quality ECE, help families find high-quality care, and help providers develop high-quality programs, there must be some shared definition of quality. Furthermore, in order to understand how the system is changing in response to interventions, we must have some way to track and respond to that change.

Once quality is defined and measured, there must be pathways to improve quality. Without doing so, measuring quality may amplify the existing dynamics at play - those providers who are high-quality will attract families and funds, and those who already struggle will find it harder to attract families and resources.

An Interconnected System

The experiences of children, providers, and workers are intertwined in early childhood education. This interconnectivity makes it difficult to create lasting change when only addressing one part of the system. In order for all children to truly have access to high-quality ECE in St. Louis, we need a multi-faceted approach that addresses all components of ECE.

The interventions discussed above are not the only changes needed in order to provide accessible high-quality ECE to all children, and while this model was informed by the stories of a diverse group of business owners, teachers, nonprofit leaders, parents, and researchers, there are nuances that may have been missed. Despite these challenges, the model demonstrates the connectivity of our ECE system and allows us to learn how to intervene with caution.

The interventions discussed above are important leverage points to address, without which it will be difficult to use resources efficiently and will cause unintended, negative consequences. However, we must acknowledge both the breadth of change needed and that the system will be resistant to change until many interventions are in place and running. It will certainly take time and resources to do all that will be necessary. As momentum grows in the region and across the nation, we must continue reevaluate, recalibrate, and see how to respond to a changing system moving forward.

NOW WHAT?

The system is complex and coordination across the region is necessary. If you’re unsure about your role, check out the following ways you can engage with what’s happening in STL:

Sign up to learn more about the First Step to Equity Collaborative.

Visit and download the ECE Playbook created by our partnership with the WEPOWER Tomorrow Builders Fellows.

Read other reports about this work from our key partners.

Partners

A special thanks to our nonprofit/corporate partners; school administrators; teachers; and parents who have played a vital role of informing our work over the past three years. Without your input, none of this would be possible.

System Dynamics

We shape education realities for children, by understanding current systems +

strategies through rigorous research.